The following is a shorter version of a chapter I contributed to Translating Dissent: Voices from and within the Egyptian Revolution, ed. Mona Baker, out now via Routledge and available for purchase. This content has been edited for brevity.

In 2013, I gave a talk at the Petrie Museum in London to an audience of Egyptology students and academics. I presented the work of Alaa Awad, a 33-year-old Egyptian street artist who had painted murals of ancient Egyptian art around ahrir Square during the political protests of 2011 and 2012.

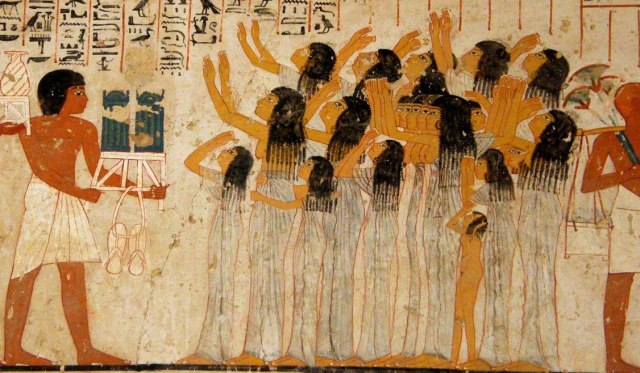

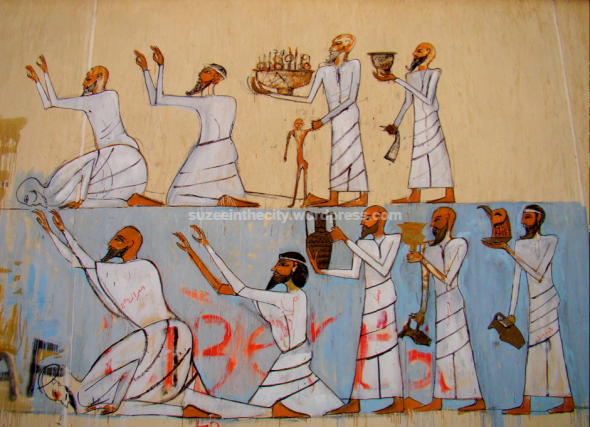

As I showed them a series of murals depicting women in fierce, coloured robes walking to battle, or a row of bearded men kneeling before the throne of a mouse being fanned by a cat, I could sense the room temperature changing as they began to realise that the paintings were almost perfect replicas of the ancient Egyptian murals they had studied.

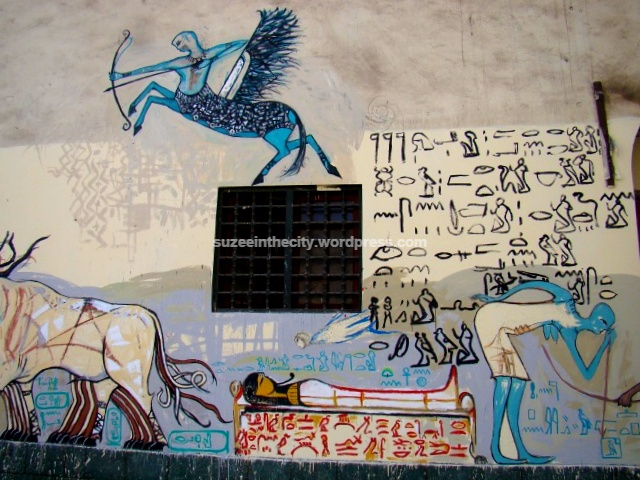

Why had these murals reappeared? What was Awad trying to tell us? He seemed to have put a lot more thought into the symbolism, relevance and context of his murals than many of his peers, making his work somewhat more resistant to translation. He chose to paint shapes that were immediately recognizable as part of our historical identity, yet completely alien at the same time – at least to those of us who had not studied Ancient Egypt and were not familiar with temple names such as Ramose, Ramesseum and Khonsu, or the significance of black lotuses, green goddesses, or the Book of the Dead’s weighing of the heart.

A classically trained artist born in Mansoura, Awad lived on the West Bank of Luxor in Upper Egypt, where he taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts alongside fellow street artist Ammar Abo Bakr. Both artists had training and skills that gave them a significant advantage over the many street artists I had seen emerge, and yet they were polar opposites.

In February 2012, Awad and Abo Bakr took an eight-hour train from Luxor to join the Port Said massacre protests on Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cairo. They spent fifty days painting on the walls of the American University in Cairo and the neighbouring Lycée School; these walls provided a popular canvas for many graffiti artists at the time, especially because of their proximity to Tahrir Square. The outcome was a 100-metre long mural: Abo Bakr painted martyrs with wings, while Awad flirted with tombs, scales, feathers and suckling women. His work was bizarre, ethereal and somehow strangely discomforting.

While Abo Bakr created direct, confrontational and easily dissected murals, while he painted decontextualized forms and faces that neither resembled nor related to contemporary Egyptians aesthetically and culturally. Abo Bakr and his peers reflected the revolution in their work, but Awad’s art revealed a quieter and more intellectual battle.

His themes were tackled subtly through visual codes and an ancient language. He took familiar images that surrounded Egyptians – on advertising billboards, one-pound notes, restaurant menus and schoolbook covers – and placed them in a different, contemporary context, surrounded by broken glass and shrapnel-filled walls that made the murals look so out of place; they demanded that we stop, stare and think about their relevance.

It was – to me at least – the equivalent of placing a gold-framed Michelangelo fresco in the centre of a war zone, bringing two disconnected worlds together into a surreal co-existence.

Awad made work that he hoped people would think and argue about; and those clever enough to recognize his shapes as forms of dissent and resistance felt pleasure in being let in on his secret. You could see the subtlety of his themes in the naked, dark haired women holding shields as they climbed a ladder, in the crying faces of mothers begging the star-filled skies, and in the black panthers roaming a battlefield filled with crushed and bloodied bodies writhing like snakes.

He changed tiny details, such as giving the row of women batons to protect themselves, transforming the Pharaonic mural from one originally depicting mourners to one of armed and grieving women, heading away from Tahrir and towards the Ministry of Interior on Bab El Louk. This was a strategic decision: he had painted this after the police-aided massacre of the Ahli Ultras at the Port Said match on 1 February 2012, and at a point when protesters filled the streets and attempted to fight their way towards the Ministry of Interior building, the aorta of the Egyptian Police.

In another mural, he painted the Goddess Hathor, a goddess of love and motherhood, suckling a young and sickly boy next to scales that carried a feather on one scale and a heart being placed on the other. This is the weighing of the scale from the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, where the jackal-headed god Anubis weighs the heart of the deceased against a feather. If the heart weighed heavier, the deceased is condemned to non-existence.

But Awad explained to Mona Abaza (2012b) that the Goddess Hathor represented Susanne Mubarak, wife of the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, whose sickly sweet name ‘Mama Susanne’ had been spoon-fed to generations of Egyptian children via the nationalistic media. This changed the whole mural; yet no one would have known this if Awad had not actually explained it himself.

Awad spoke of his frustration about the lack of justice in Egypt, its hypocrisy and corruption. The Mubarak family’s appearance next to the scales of the afterlife could be his commentary on the double standards of the justice system in Egypt, where the Mubarak clan are now free, while thousands of activists and journalists have been jailed, disappeared, or given maximum sentencing.

He spoke of identity often. You could see it in his work. His pride and patriotism were reflected in his relentless need to paint larger than life replicas of his ancestors. He wanted to remind the street of what the real, original Egyptians were like: flowing hair, naked heads, fierce and tall; not religious zealots crouching before a tyrant.

The mural from the tomb of Sobekhotep (18th dynasty) got Awad into particular trouble. In painting a row of bald and bearded men praying to and making offerings to a mouse on the throne, Awad seemed to be mocking religious zealots and members of the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi parties. His timing was perfect; he painted the mural in late 2012, at a time when religious parties were gaining political power, a situation that generated distrust and frustration among secular protestors.

As he painted, I remember a crowd of men – mostly bald and bearded, wearing the traditional galabeyas, often associated with fundamentalist Muslims – surrounding him, alternating between protesting, pleading and assaulting him. He kept his cool and pointed out that he was merely depicting a mural from an ancient tomb as a tribute to our ancient Egyptian history. Baffled, his critics eventually left. He may have won that battle, but he didn’t necessarily communicate his meaning to the viewer.

Without Awad to explain it, or the Weighing of the Heart, or the Mama Suzanne reference, none of these paintings translated easily. He created barriers between his murals and his audience through his use of ancient symbols. The only people who could possibly decipher his work were Egyptologists, or academics familiar with ancient Egyptian art and hieroglyphics. Not me, not the bearded men, not the average Egyptian walking to work past the murals every morning.

He spoke with a composed dignity. Whenever we met by his ladder on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, he was usually surrounded by Western reporters and filmmakers, documenting him in action and cooing audibly at his work. He never lost his cool, never swore in front of me, and often would turn his head to exhale his cigarette smoke away from me. A former army conscript, he wouldn’t speak a word against the conscripts that he once stood next to. He found fault in the leaders of the country: religious, political and military, they were all corrupt. His great enemy was not the state or the religious fanatics, not even the police that he threw rocks at between painting through tear gas, but foreign interference. I heard this term repeatedly throughout our conversations on the street, in coffee shops, on the plane, in foreign countries where he travelled to speak of his work and paint more murals.

Awad once showed me his mural of Tutmose III, a king towering over his captives and holding them by their hairs, as he raises his other arm to smite them. He wrote on the painting in Arabic: ‘I am the Guardian of the Eastern Gates; the herders shall not pass again’. The threat is from the East, he tells me, our borders are weak, and our very existence is being threatened from the East.

In mid-2012, the Scientific Institute in Tahrir caught fire during a protest and burned down, destroying hundreds of precious manuscripts, including an original copy of Le Description de l’Egypte, a seminal book that provided the basis for much of our current knowledge about ancient Egypt, but also perpetuated French colonialist thinking as well as the idea that Western countries had superior knowledge about Egypt’s heritage than Egyptians themselves (Lau 2012-2013). Before the Institute burned down, few had heard of its existence.

The building was shut to the Egyptian public, and thus its books, supposedly the property of the people, were completely inaccessible. On the corner of the charred building, a military blockade had been erected. Awad painted a landscape mural of the West bank of Luxor on the new wall, with two-dimensional silhouettes hidden in the shade. On the side closest to the building he wrote (in Arabic): ‘There is no such thing as Le Description de l’Egypte. Let us see the light’.

Whether the last sentence was a plea for the walls to be pulled down or for the books to see the light of day, I don’t know. What I am certain of is that Awad rejected the book’s orientalism and the very concept of ‘superior knowledge’ being the preserve of the West. He certainly didn’t mourn the loss of the book, and believed that the murals he painted would restore a sense of agency in people and reconnect them to their history (Lau 2012-2013). I don’t know how he did it or whether he consciously planned it, but at dusk, when the street lamps were switched on, golden light spilled through the cracks in the wall and Luxor’s landscapes and its silhouettes came to life.

He talked in riddles, like a faded history book. Over coffee and cigarettes, he peppered his chit chat with anecdotes about ancient Egypt, black lotuses and oxen, mourners’ hands covered in mud and candles being raised to the skies and the Salafists he would stand up to whenever they tried to stop him from painting. Then he asked me to pass the sugar. Yet always we returned to the fear and paranoia, the neurosis in his agile mind about foreign forces, be it Israel or the American University in Cairo, colonialists or the orientalists.

What’s left of the wall today, Khonsu temple at Karnak, Luxor

His work excited my audience at the Petrie Museum because he had followed the same format of painting as the ancient Egyptians once did; painting stiff figures in almost perfect symmetry on straight lines to create a perfectly controlled painting that seemed to be held by a frame – as opposed to the freehand graffiti and almost volatile spurts of colour on the walls around him in Mohamed Mahmoud Street and elsewhere in Cairo.

In his battle scenes on the corners of Kasr El Eini and Yousef El Guindy Street in downtown Cairo, he also painted without registers – straight lines that create an invisible frame and a symmetry to the image – to specifically evoke chaos, battles and hunting scenes (Calvert, n.d.). He painted kings and gods on the same scale to represent their power and holiness, but he changed a subtle detail: by painting the mourning women the same size as the gods and kings in other murals on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, he gave these women the same power and hierarchy as deities and rulers, in an attempt to pay tribute to their spirit and bravery.

Awad’s simple yet terrific strategy of transferring art from a means of supporting the status quo and propaganda intended to glorify the ruling pharaoh to a street performance that subverts the established art form and empowers anti-regime protests in modern-day Egypt was practically a rewriting, a retranslation of our past. By decontextualizing the murals and changing subtle but important details, he took something away from the state – something that had upheld the sanctity of the state – and gave it back to the people. But did they get it? Did it translate, even within the same cultural environment?

There I was, talking to a room full of expert Egyptologists, surrounded by books and artefacts in glass casings that had been removed from my country’s temples and studied around the world. I spoke to them about Pharaonic temples and icons, explaining things that they already knew but I had needed several hours of research to decipher. The irony that I, as an Egyptian, was showing codes I did not understand to a group of foreign experts inside a space full of acquired antiquities was not lost on me.

I had started writing about street art in Cairo in 2011 because it simply fascinated me. There was no agenda, no book project, no long-term plan, I just wanted to write and photograph graffiti. I befriended several artists in Cairo. I tagged along as they worked, watched as they were interviewed, and listened when they complained that their work had been stolen or defaced and their words taken out of context.

In some way, I thought of myself as a translator – one who turned images into text, gave background to walls, and explained to an English-speaking world why a massive mural of a Koranic verse, the face of an angel-winged man, or a gas mask covering the face of Nefertiti mattered. In contextualizing and translating the walls, in sharing what I had heard on the street and how people had reacted to the art, I felt I was doing some, albeit minor, service to someone, somewhere.

It often worried me how words and images can be taken out of context, misunderstood, misconstrued. Because I wrote consistently about street art on my blog, sometimes people would take my word for it when I said something looked good or bad. No matter how often I stated it was my personal opinion, somehow I would find my writing appear elsewhere as a fact. And that terrified me.

The word ‘expert’ had been flung around so overzealously in Egypt by that time. It seemed that anyone with a degree or an accent or a hat was an authority on Egypt, and anyone who spoke English and knew how to explain the writing on the wall could be a primary source of information, a translator of momentous events. It worried me that a substantial part of the narrative was being written by people who had not set foot in Egypt, and relied on fixers or translators like me to provide the basis of their arguments.

The word ‘expert’ was handed out so carelessly that one day I found myself giving a talk at the Petrie Museum, trying to explain an ancient art piece I did not fully understand to an audience that didn’t know what had happened the night Awad had started painting, the crying, the tear gas and the gunshots as police stormed the field hospital held in a mosque across from Mohamed Mahmoud Street during the Port Said protests, stepping on dying bodies in their boots. The difference between an expert and me was that I was too close to the subject to talk without bias. I could not remove the murals from their contexts, whereas these anthropologists and historians were comparing them to the ancient contexts they were familiar with.

One of the reasons why I find the word ‘expert’ distasteful is that it gives me a responsibility I do not want to assume. In the days I spent photographing graffiti and speaking to artists such as Awad, it never crossed my mind to count the number of people surrounding him, or to record the different reactions, count them and then divide them by square metre population of the area. As an observer, I was able to appreciate and share the street’s reaction; I felt part of it and I lived it. To quantify that would mean to take a step back from Awad and his peers, and observe from an anthropologist’s perspective. I had no interest in being distanced from the context; it would have rendered the art much less evocative.

I identified the cause of my discomfort at having spoken at Petrie in Lau’s paper on Le Description de l’Egypte (2013-2014) and the Scientific Institute, in which she argued that such establishments excluded the Egyptian people from their own heritage and gave currency to a concept of colonialist superiority that – to this day – I still experience whenever I visit a foreign museum exhibiting Egyptian antiquities. Perhaps one of the factors that made Awad so exciting to the Egyptologists, academics and me is the threat he posed to the notion of expertise, including the expertise of the translator.

He was a native who studied and identified with Ancient Egyptian art and history, he knew how to manipulate ancient texts and symbols into awe-inspiring art, and he studied historical interpretations such as Le Description de l’Egypte, rejecting them as colonialist and flawed. So he wrote his own version, and hoped that others would read, understand, and if necessary translate it – as best they can – for those who can’t interpret it for themselves.

References

Abaza, Mona (2012b) ‘The Art of Narrating the Egyptian Revolution: An Interview with Alaa Awad’, Jadaliyya. Available at http://vimeo.com/40476138 (last accessed 10 November 2014).

Calvert, Amy (n.d.) ‘Egyptian Art’, Khan Academy. Available at http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/egyptian-art-an-introduction.html (last accessed 19 November 2014).

Lau, Lisa (2012-2013) ‘Mohamed Mahmoud Street: Reclaiming Narratives of Living History for the Egyptian People’, WR: Journal of the CAS Writing Program, Issue 5. Available at http://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-5/lau/ (last accessed 29 October 2014).

Reblogged this on maha's place.

Pingback: Duke Prof: Feminist 'Soft' Jihad a Force for Peace

Pingback: Duke Prof: Feminist ‘Soft’ Jihad a Force for Peace The twisted fantasy world of Prof. Ellen McLarney. March 2, 2016 Andrew Harrod | RUTHFULLY YOURS

Pingback: Duke Prof: Feminist ‘Soft’ Jihad a Force for Peace | The Counter Jihad Report

Pingback: 5 artistas en Egipto que te harán salir a la calle – Va de arte!

Pingback: A new mural in Cairo covers more than 40 buildings. The result is stunning. – hihihi.lol

Hi there, my name is Abbey and I am doing a research project in my high school. I would love to get the chance to ask you some questions in regards to some of the topics you have discussed in your blog. Please contact me at letsmileslast@q.com Thank you so much!